Bedrock - from code to production

Introduction

Bedrock is the code name for the project that runs www.mozilla.org. It is shiny, awesome, and open source. Mozilla.org is the site where everyone comes to download Firefox, and is also the main public facing web property for Mozilla as an organization. It represents who we are and what we do.

Bedrock is a large Django app that has many moving parts, with web pages translated into many different languages (99 locales at time of writing!). This post aims to follow a piece of code through the development lifecycle; from bug, to pull request, to code review, localization, and finally pushed live to production. Hopefully it may prove insightful and give some things to think about when requesting changes or creating new content.

Note: A presentation was given on this topic. The slides and video from that event are online.

The change request

All development work should start with filing a bug. Bugzilla is our tool of choice for tracking changes, and links to bugs can be found throughout our commit history for reference. This gives us a paper trail for when and why changes were made. For a site that has existed over many years, this is very useful.

A well written bug should provide a clear summary, and provide as much additional information that may be relevant to resolving the bug. If the bug is reporting an error or mistake on a web page, providing clear steps to reproduce is a great start to helping it get fixed quickly. MDN has an excellent set of guidelines for bug reporting with a lot more detail.

An example bug summary for creating a new web page might be like so:

Please create a new Firefox download page at the following URL:

https://www.mozilla.org/firefox/example-download-page/

Page assets are linked below:

[link to design file]

[link to copy file]

The download page needs to be live in production by: 1 April, 2017.

Locales required for translation on launch: en-US, de, fr, es-ES.

If a bug is requesting the creation of new content or updates to existing content, related design and copy assets should be linked directly in the bug. For time sensitive requests, a clear due date should also be provided.

If a change requires localization, it also needs to be clearly stated. Our web pages are translated by teams of volunteers, so adequate time and warning must be given if there are hard deadlines involved. We will not show untranslated text to non-English locales on our web pages.

Once a bug has been triaged and contains enough information to act on, it can be assigned to a developer. When a bug has been assigned, any changes or feedback should be added directly to the bug (email is a great place for information to get lost).

Creating a new page

When we’re ready to start working on our bug, we first create a new feature branch on the bedrock GitHub repo. This allows us work on the bug in parallel to all the other changes landing in the master branch of the the repository. You can learn more about git workflows using GitHub’s introduction guide.

Creating a new page on bedrock is pretty simple. All pages are built using the Jinja template engine, inheriting from a common base template. This base template scaffolds out everything we need to start creating a new page. Then it’s just a case of adding in content and any additional styling or behavior the page might need.

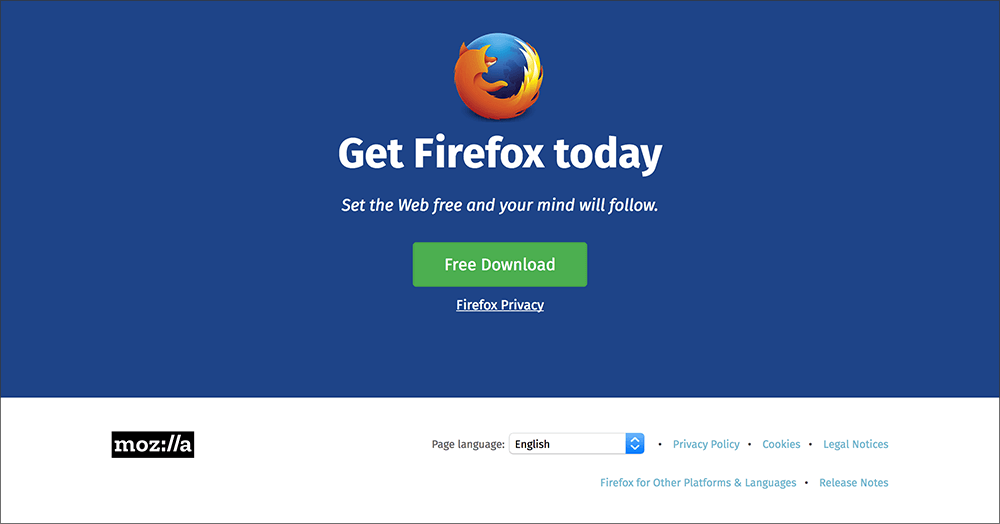

When we’re finished creating our new template and adding in content, our example download page might look something like this:

Because our example page inherits from a common base template it automatically receives the following characteristics:

- Responsive and mobile-first by default. All pages should be designed with responsiveness in mind. Designs that start with small (mobile) viewports first and then expand up toward desktop sizes work better than the other way around.

- Page component styling using Pebbles; our own lightweight CSS framework. Pebbles consists of a shared library of styles for common elements that appear throughout the site (e.g. page headers, navigation, footers, email signup forms, download buttons). Working with common design components allows us to create and update pages quickly.

- Pre-built for localization (l10n). All pages are coded with strings wrapped ready for l10n. This means that copy and visuals should be suitable for different languages and designed to work well with variable length strings.

- Built-in platform detection for Firefox downloads. We go to great lengths to try and make sure users get the correct binary file for their operating system and language when clicking on a download button. All pages get this logic for free should they need it.

- Privacy friendly. We work hard to make sure all our pages respect user privacy as much as possible. We support Do Not Track (DNT), so users with this enabled are not tracked in Google Analytics or entered into Firefox Desktop Attribution. They will also not be entered into A/B experiments using libraries such as Traffic Cop.

- Security focused. We enforce an active Content Security Policy (CSP) that limits the scope of third-party content allowed to run on the site. This aims to protect our users from security attacks and also helps ensure the integrity of Firefox downloads. It is a critical feature for our visitors.

- Built using progressive enhancement and with accessibility in mind. User experiences need to work well with keyboard, mouse and touch, and work well with screen reading software. Pages should still function or degrade gracefully even if JavaScript fails, or is disabled by the user.

A note about browser support

Bedrock currently supports first-class CSS and JavaScript for all major evergreen browsers, as well as for Internet Explorer 9 and upward. Internet Explorer 8 and below get a simplified, universal stylesheet. This ensures that content is readable and accessible, but nothing more.

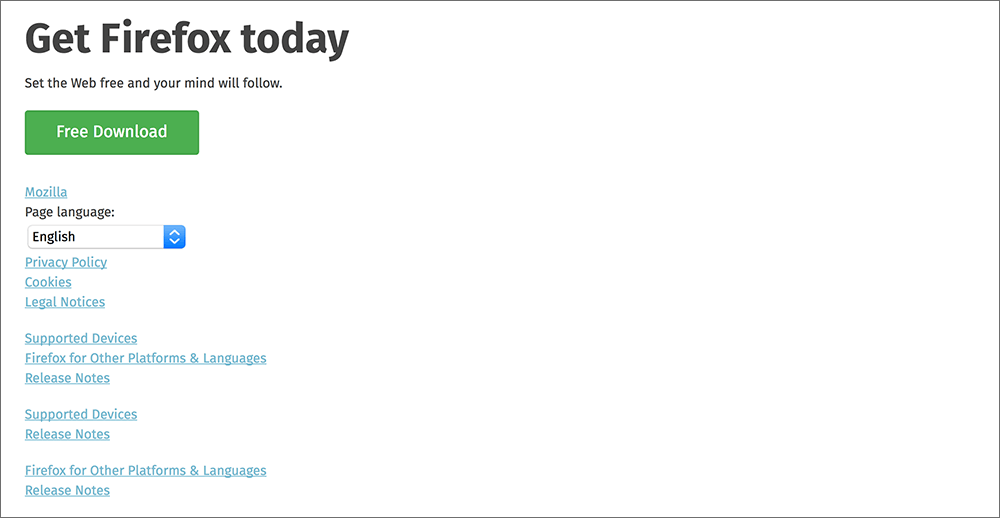

Here’s how our example download page might look in old browsers:

Not much to it right? The key here is that all the page information is still perfectly readable and accessible, meaning the user can still accomplish their goal. By providing a more basic set of styling to older browsers, we are free to use more modern web platform features in order to accomplish more sophisticated designs and experiences.

Special considerations for download pages

For critical download pages such as our example page, we still need to ensure that users can successfully download Firefox, even in older browsers. When the user clicks the download button, they still need to receive the correct file for their operating system and language.

Because of this added support requirement, download pages may require additional testing and QA. For really high traffic pages such as /firefox/new/, we may still make extra effort to provide a higher level of CSS support to older browsers. The pages won’t look exactly the same, but they should still degrade gracefully.

Localization (l10n)

Many mozilla.org pages are translated into multiple languages. While much of our marketing focus is primarily for English language locales first and foremost, non-English traffic actually makes up around 60% of our overall site traffic. Unless there is a specific request for a page to be in English only, we create all pages assuming they will be translated should our volunteer community wish to do the work.

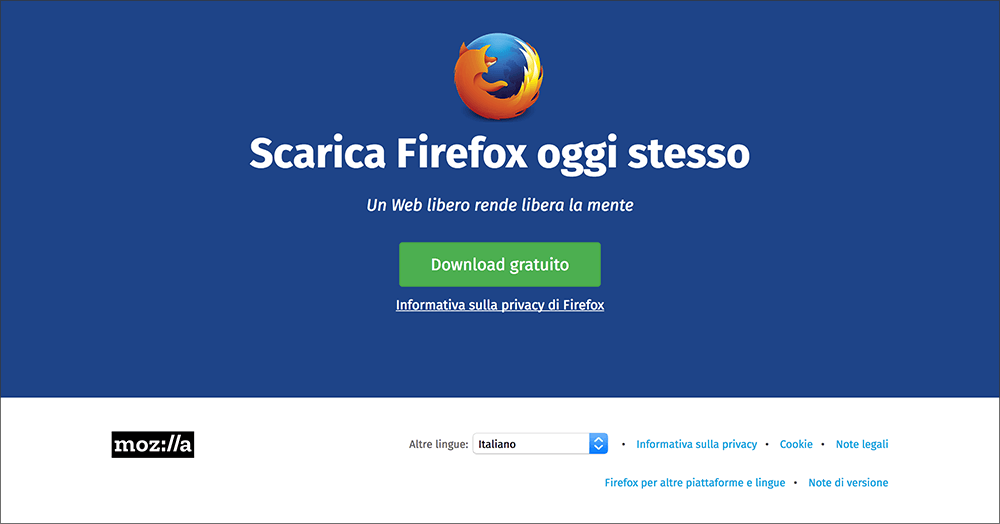

Here’s how our example download page might look in Italian:

Because our translations are done by volunteers, we try our best to minimize the number of string changes we ask them for. If a page is translated in over 40 locales and we change one string, that still requires 40 new translations to be made. If strings are changing every week, this can begin put a lot of strain on the goodwill of our community. To minimize this churn we try to:

- Only change strings if absolutely necessary.

- Try and batch up string changes to send out in one go.

- Reuse existing strings that may already be translated (if similar to what’s being asked for).

- For new or redesigned pages that need to be translated for a set launch date, we typically ask for a lead time of 3-4 weeks.

Of course, each time we change a string on an existing page, we can’t always wait 4 weeks before merging the change. For situations like this we often use an l10n conditional tag in the Jinja template. For example, if we wanted to change the main heading on our download page we could do:

<h1>

{% if l10n_has_tag('page_heading_update') %}

{{ _('Download Firefox today!') }}

{% else %}

{{ _('Get Firefox today') }}

{% endif %}

</h1>

This allows locales to opt-in to the new translated string one by one, else they fall back to the original string.

We can also do this type of thing for entirely redesigned pages in our view logic, so locales only see the new design once they have it translated.

def example_download_page(request):

locale = l10n_utils.get_locale(request)

if lang_file_is_active('firefox/example-page/redesign', locale):

template = 'firefox/example-page/redesign.html'

else:

template = 'firefox/example-page/index.html'

return l10n_utils.render(request, template)

Doing this does still come with technical debt of course, as the old content, conditional logic and .lang files still need cleaning up later on, once everyone is using the new translations.

GitHub pull request

Once our page is coded and we’re ready for the next step, we can open a pull request on GitHub. Once this is done the following things typically happen:

- Our continuous integration service, CircleCI, runs a series of automated checks on the pull request. This runs unit tests as well as checks the code for both syntax and style errors. Running these automated checks saves us significant time during code review by picking out routine errors.

- The pull request must then be code reviewed by another human. Every code change gets reviewed by at least one other developer before merging.

- If the change requires localization, strings are extracted from the branch and checked by our l10n team. If they look good, they are sent out to our volunteers for translation. Once this has begun, it is very bad to make a breaking change to a piece of copy.

- Once the pull request is approved by a reviewer, it can then be merged into the master branch and automatically deployed to our dev environment.

Other useful things to know about

Demo servers

Sometimes we’d like to have a URL we can give people to demonstrate changes that aren’t yet live on the site and that aren’t yet ready to be merged into our master branch. We’ve enabled this via our Jenkins CI server and Github. A developer that would like to demo their changes has only to follow these steps:

- Push their git branch to the primary repository using a special branch name.

- Branch name must start with

demo__and then be any letters, numbers, and dashes (e.g. demo__the-dude)

- Branch name must start with

- Profit

That’s really it. Jenkins will build the demo and if it is successful a notification in our IRC channel will inform the developer of their new demo’s URL. Feel free to check out how that works if you’re curious.

A/B testing

For A/B testing bedrock has two options available, Traffic Cop and Optimizely. Jon wrote a great blog post on the pros and cons of using each solution so we won’t repeat them here. You should go read it.

Analytics

Analytics on bedrock are provided using Google Tag Manager (GTM). Most of bedrock’s shared components and pages are pre-built for analytics using common event handlers and data attributes. We can also create and fire custom events as required.

GTM on bedrock is implemented in such a way that it respects DNT, and user experiences should not break if tracking protection or content blocking software is installed.

Feature toggling

Product deployments are easier than ever for bedrock, but they’re not and likely will never be without risk. There is also much that could go wrong (at AWS or any of our networks) that could prevent a production deployment from being successful or timely. Therefore we have developed the ability to use environment variables as feature switches. These allow us to simply update the running environment of the bedrock servers via the Deis command-line utility, and the site will react to those changes without the need for us to deploy new code.

These switches are very useful in situations that require precise timing, or modification of the site on off hours when support for a failed deployment would be light to nonexistent. We’ve used them for announcements that need to be timed with announcement publications elsewhere, or stage events at gatherings like Mobile World Congress.

Deployment

We deploy production fairly often, and we deploy to our dev instance on every push to our master branch.

We are capable of deploying production many times per day, and like to deploy at least once per day.

When any of our development team is happy with what is on dev and ready to deploy to production, they have only to follow these steps:

- Check the deployment pipeline to make sure the latest master branch build was a success.

- Add a properly formatted git tag (e.g. 2017-02-28.1) to the latest master commit, and push that to the

prodbranch.- This can all be accomplished automatically by running

bin/tag-release.sh --pushfrom the project.

- This can all be accomplished automatically by running

Once this is done, Jenkins will notice that a change has been made to the prod branch that has been appropriately tagged,

and will start its deployment process:

- Build the necessary docker images

- Test said docker images

- Python unit tests

- Selenium-based smoke tests run against the app running locally

- Push docker images to public docker hub and our private registries

- Tell Deis to deploy the new docker images to the staging app in our Oregon AWS cluster

- Run our integration test suite against the staging instance in Oregon

- Our full selenium test suite run against multiple browsers (Firefox, Chrome, IE, etc.) in Saucelabs.

- Repeat steps 4 and 5 for prod in Oregon, then for stage then prod in Ireland.

If any testing phase fails we are notified in IRC and the deployment is halted. The whole process usually takes around an hour.

A deployment to our dev instance is very similar to our production deployment (above).

The primary differences are that it happens on every push to master, and fewer integration tests are run against the deployed app.

Our dev instance is also slightly different in that the DEV setting is set to True, which primarily means that a development

version of our localization files is used so that localizers have a stable site from which to view their work-in-progress, and

all feature switches are on by default.

Environments

Our server infrastructure is based on AWS EC2 running CoreOS instances in a Deis v1 cluster. Those words may not mean much to you if you’re not into server ops, but it basically means that we use Amazon’s cloud computing resources to manage our servers, and Deis is a FOSS Heroku clone that allows us a developer friendly deployment flow. We hope to soon move to Deis v2 on top of Kubernetes while staying at AWS, but for now v1 is what we’re using.

We have three primary instances of the site: Dev, Stage, and Prod. They are all comprised of deployments in our 2 primary Deis clusters in Oregon (US) and Ireland (AWS us-west-2 and eu-west-1 regions respectively).

- Dev: https://www-dev.allizom.org/. Deployed on every commit to our

masterbranch. - Stage: https://www.allizom.org/. Deployed and tested on every tagged commit to our

prodbranch. - Prod: https://www.mozilla.org/. Deployed and tested on every tagged commit to our

prodbranch.

The primary domain for both stage and prod points to our CDN provider, which in turn points to another domain hosted in AWS Route53. This domain uses latency-based routing to send clients to the fastest servers from their location. So each node at the CDN should get routed to the closest server cluster to it. This also means that we get automatic fail-over in case one cluster goes down or starts throwing errors.

Conclusion

Whew! That’s a lot of information to take in. With any luck, our example page would now be magically deployed in production after going through the pipeline. Our process for deployment may sound a bit complicated, and that’s because it is. The reason we’ve built this kind of automation is so we can remove as many manual steps as possible, saving us time and also helping us to deploy with greater speed and confidence.